Background

There has been growing recognition of inequities in access to green space. Five key indicators broadly control the extent of the wellbeing benefit an individual derives from green space: greenness, proximity, quality, accessibility, and frequency of use.

West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) has ambitions to support its constituent local authorities to make targeted interventions that:

- Improve green space provision.

- Mitigate climate change.

- Tackle wellbeing inequalities exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

NEF Consulting was commissioned by WMCA to investigate the intersection between green space access and social inequity, and to develop an approach to targeting interventions.

Approach

Our exploratory analysis focused on:

- Physical barriers, population pressure on green space and proximity to green space.

- Social/demographic characteristics such as socioeconomic deprivation, age and ethnicity.

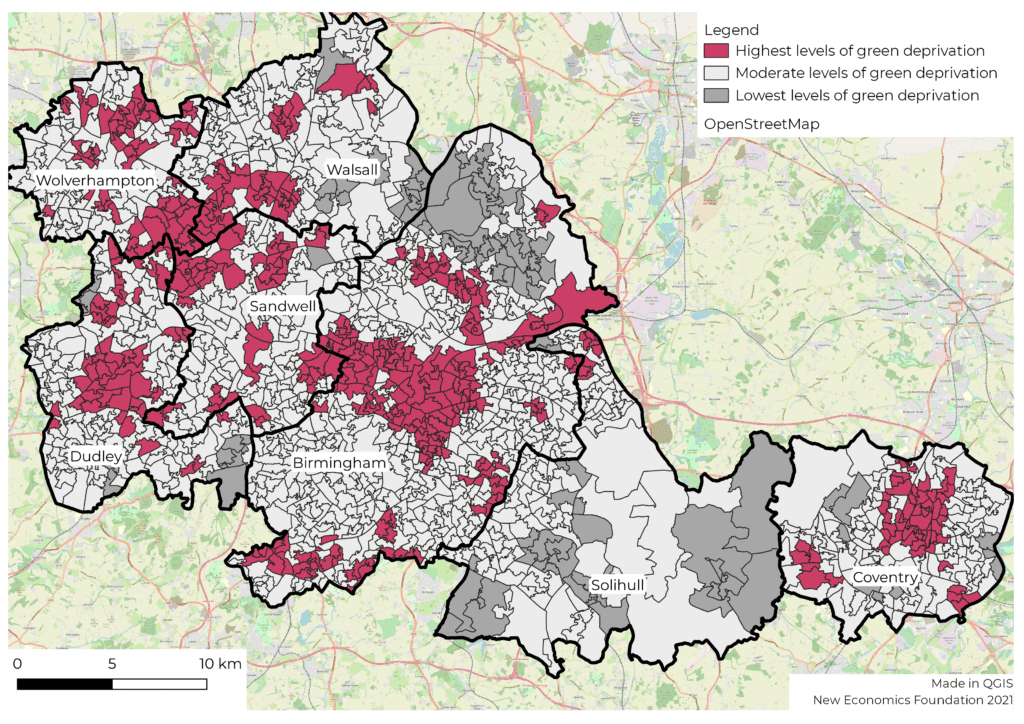

We developed maps to visualise ‘hotspots’ of socioeconomic characteristics and poor green space access.

We conducted a literature review of relevant interventions outside the West Midlands region to offer ideas for tackling the challenges and barriers of access to green space in ‘hotspot’ areas.

Findings

The exploratory analysis found:

- Walsall and Birmingham rank relatively high for absolute park space when compared with other local authorities. However, all seven LAs in WMCA rank very low in terms of relative park space per person.

- There is a strong correlation between population pressure and socioeconomic deprivation. A high level of deprivation correlated with greater population pressure on green space. However, communities with high levels of deprivation were typically closer to green space.

- Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) populations in Birmingham, Coventry and Walsall showed greater population pressure on green space than non-BAME populations. Many BAME populations are also experiencing high rates of deprivation.

- Broadly, older populations experience less population pressure on green space in comparison to younger populations, but are also often further away from green space.

Hotspot areas of poor green space access

While headline findings present a common trend across the West Midlands, the purpose of the analysis was to identify particular ‘hotspot’ areas with poor access to green space. Through our mapping approach we identified many areas where the above issues and inequities are particularly acute. We also identified areas where issues might be hidden by the aggregate analysis, for example locations where a large young population is also particularly far away from green space.

The literature review presented intervention ideas categorised as:

- Re-purposing space / creating new spaces: Ideas include regenerating brownfield sites, creating pocket parks and accessible rooftops.

- Infrastructure for travel and connectivity: Consideration of how people would reach green spaces. Examples include green corridors, cycling networks, public transport and walking routes.

- Enhancing existing space: Active management of green spaces, improving biodiversity, preserving heritage and inclusion of facilities or multi-functional uses.

- Greening space: The wellbeing generated by an urban space goes beyond parks, and can be enhanced through the broader ‘greenness’ of the area. Examples include tree planting and creation of “living” walls on facades and roofs.

Next steps

To understand in more detail any deficits in green space provision we would need to go into more detail on the types and functions of the green spaces available. It is important to engage with local communities to further explore their green space usage, the barriers, and what they want from their local green space.

There are a range of possible interventions, from the creation of a new park to a community vegetable patch. Ideas for ‘hotspot’ areas inlcude:

- Creating a West Midlands Green Spaces Taskforce. A strategic approach co-ordinated by representatives from the local authorities. The group should involve individuals from a variety of departments such as public health, transport, and cultural services to ensure a holistic approach.

- Building on the evidence base to prioritise ‘hotspot’ areas. Further research to identify the relationship between green space, socioeconomic characteristics, and physical barriers to accessing green space.

- Involving residents. Qualitative evidence gathered from residents will enable WMCA to dig deeper into the issues highlighted by the data.

- Data sharing platform or designated data officers. To ensure consistent data collection, and the sharing and monitoring of data.

- Capacity building and sharing best practice. To build on learnings from other local authorities and to set out ways of working to enable greater collaboration, effectiveness and efficiency. This has been done in Greater Manchester as part of the Bee Network.

- A Community Green Grant Fund targeting ‘hotspot’ areas. To improve access to green space and tailor interventions to local context.